August 8, 2025 – For millions of people living in the world’s tropical and subtropical climates, the annual battle with oppressive heat is a familiar struggle. As temperatures climb, the immediate response is often to seal the windows and turn on the air conditioner, leading to skyrocketing electricity bills. However, a brilliantly simple diagram circulating online reveals a powerful truth: the key to a cooler home may not lie in more technology, but in smarter design—a principle that many modern buildings have unfortunately abandoned.

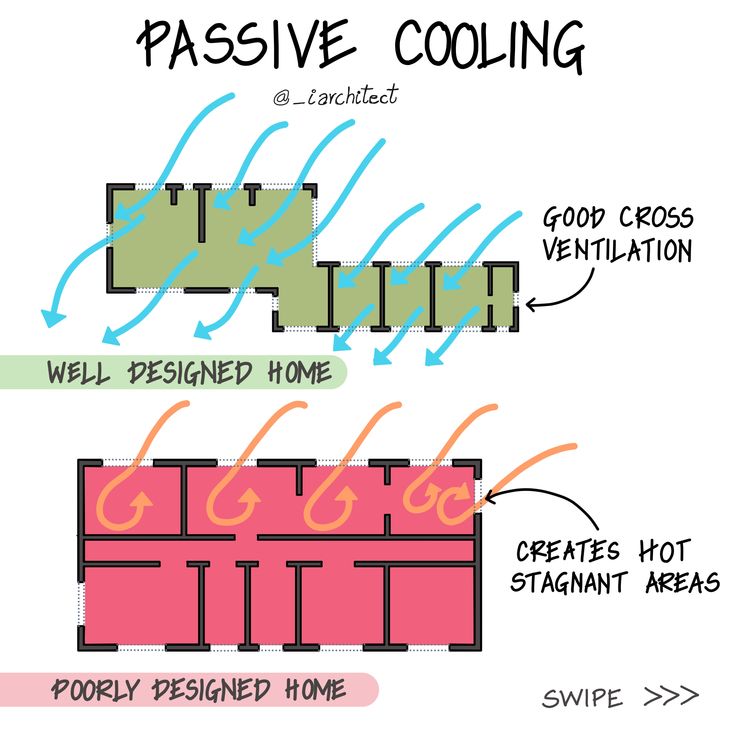

The image, created by the architecture-focused account @_iarchitect, uses a clear, step-by-step visual to contrast two basic home layouts under the heading “Passive Cooling.” It’s a concept that illustrates how architectural choices directly impact our comfort, energy use, and quality of life.

Step 1: Decoding the Viral Diagram – The Tale of Two Homes

The diagram’s effectiveness is in its simplicity. It first shows a “Well Designed Home.” This layout, shaped like an ‘L’, is designed with windows and doors on opposite sides of its rooms. A series of clean blue arrows demonstrate how this arrangement allows air to flow freely through the space. This is “Good Cross-Ventilation,” a natural process where incoming breezes push warm, stale interior air out, creating a constant, cooling current.

Directly below is the “Poorly Designed Home.” It’s a deep, rectangular box where the rooms at the back have no windows or connection to the outside. Here, the arrows are a chaotic orange, swirling in place. These, the diagram explains, are “Hot Stagnant Areas.” Without a path to escape, the air in these rooms is trapped. It absorbs heat from sunlight, appliances, and occupants, turning bedrooms and living areas into uncomfortably warm zones.

This simple comparison effectively diagnoses a widespread problem felt by residents in countless modern apartments, townhouses, and tract homes around the globe.

Step 2: Correcting the Common Mistake in Modern Global Construction

The fundamental “mistake” that the diagram highlights is not a single error but a systemic oversight in contemporary building practices, particularly in regions that experience high heat. For centuries, traditional vernacular architecture across the globe evolved in harmony with local climates.

“Look at the traditional housing in virtually any hot climate—from the courtyards of the Middle East to the stilt houses of Southeast Asia or the verandas of Latin America,” explains Dr. Elena Vance, a fictional expert in tropical architecture and sustainable design. “They all share core principles of passive cooling. They are designed to manage sunlight and maximize airflow. Features like elevated floors, breathable materials, shaded outdoor spaces, and strategic openings are not just decorative; they are sophisticated climate-control systems.”

The error, Dr. Vance argues, arose from the global proliferation of a one-size-fits-all approach to construction. “The ‘poorly designed home’ in that image is a template for countless modern buildings. In the race to maximize indoor square footage, developers often create deep-plan buildings constructed side-by-side. The result is that only the very front and back of a building get airflow, while the core remains a heat trap. We started building sealed, insulated boxes designed for cold climates in regions that desperately need to breathe.”

This design philosophy forces an almost total dependence on mechanical cooling. The hot, stagnant air depicted in the diagram must be constantly cooled by air conditioning, which consumes enormous amounts of energy fighting a battle against its own poorly designed container.

Step 3: The Science and Economics of Airflow

The principle of cross-ventilation is rooted in physics—specifically, the creation of a pressure differential. Wind creates a zone of high pressure on the side of the building it hits (the windward side) and a zone of low pressure on the opposite side (the leeward side). If there are openings on both sides, air naturally moves from the high-pressure area to the low-pressure area, creating a refreshing breeze.

Dr. Kenji Tanaka, a fictional physicist specializing in building thermodynamics, explains the tangible benefits. “Properly designed cross-ventilation can reduce the perceived indoor temperature by several degrees,” he notes. “This can often be the crucial difference that determines whether a space is comfortable or requires air conditioning. Our research indicates that homes integrating passive cooling strategies can slash their cooling-related energy costs by 20% to 40%.”

These savings are not trivial. For countless households, energy costs are a major financial burden. A 40% reduction represents significant financial relief, while also reducing the overall strain on local energy grids and lowering carbon emissions. In poorly designed buildings, the trapped heat, governed by the heat transfer equation , represents a constant and avoidable expense.

Step 4: Practical Steps for Every Resident

While a complete architectural overhaul isn’t feasible for everyone, the principles demonstrated in the diagram offer valuable lessons that can be applied in almost any living situation.

For Renters and Homeowners in Existing Buildings:

- Strategic Fan Placement: In a room with only one window, place a box fan facing outwards. This will pull hot air out of the room and draw cooler air in from other areas of the house.

- Timed Ventilation: Keep windows and blinds shut during the peak heat of the day to block the sun’s energy. In the cooler early mornings and evenings, open everything up to flush the house with fresh air.

- Promote Internal Airflow: Avoid creating isolated heat traps by keeping interior doors open, allowing air to circulate more freely between rooms.

- Use Fans for Personal Cooling: A ceiling or standing fan cools you, not the room. The moving air accelerates evaporation from your skin, which is a highly energy-efficient way to feel comfortable.

For Those Building or Renovating:

- Insist on Cross-Ventilation: Make window placement a priority. Ensure that all major living spaces have openings on at least two different sides to allow for airflow.

- Incorporate High Vents: Since hot air rises, small windows placed high on a wall (clerestory windows) or ventilation shafts can act as chimneys, allowing warm air to escape naturally.

- Prioritize Shading: The most effective cooling strategy is to prevent the sun from heating the building in the first place. Use wide eaves, awnings, pergolas, or strategically planted trees to shade walls and windows.

A Blueprint for a Cooler Future

The widespread attention this simple architectural diagram has received highlights a growing global consciousness about sustainable living. It serves as a powerful reminder that we must design our homes and cities in partnership with our climate, not in opposition to it.

By re-embracing the timeless wisdom of vernacular architecture and applying it to modern construction, we can correct the costly design mistakes of the recent past. For individuals, this knowledge is a tool of empowerment, offering simple, effective ways to create more comfortable and affordable living spaces. For architects, developers, and city planners, it is a blueprint for building a cooler, more sustainable future for us all.