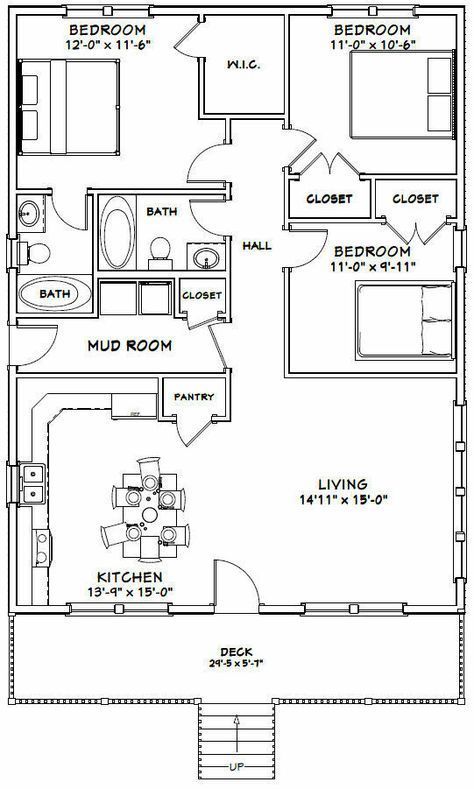

August 10, 2025 – In the booming market for compact and efficient home designs, a three-bedroom, two-bathroom floor plan is catching the eye of potential builders and buyers. On the surface, it appears to be a triumph of space-saving design, packing a primary suite, an open-concept living area, and a highly sought-after mudroom into a modest footprint.

It successfully checks all the boxes on a modern homeowner’s wish list. But a careful analysis of the home’s circulation reveals a critical and bewildering mistake. The plan, in its effort to include every feature, sacrifices the most fundamental principle of a good home: a simple, intuitive flow. This design inadvertently creates a confusing maze that would make everyday living a frustrating puzzle.

Step 1: Checking the Boxes – The Plan’s On-Paper Appeal

First, it’s important to acknowledge why this plan is so attractive at first glance. It promises a lot of functionality in a small, affordable package.

- A Full Feature Set: The design impressively includes three bedrooms and two full bathrooms. The primary bedroom is a true suite, with its own private bath and a large walk-in closet (W.I.C.).

- Open-Concept Living: The front of the house features a large, open space that combines the Living area with the Kitchen. This creates the bright, social atmosphere that is standard in new construction.

- Key Amenities: The plan includes a kitchen pantry for storage and, most notably, a dedicated Mud Room—a highly desirable feature for managing coats, shoes, and general clutter from an outdoor entrance.

- Outdoor Space: A generous Deck runs along the front of the house, extending the living space outdoors and adding curb appeal.

Based on this list of features, the plan seems to be a clear winner.

Step 2: The Critical Mistake – The Labyrinthine Layout

The fatal flaw of this design becomes apparent the moment you try to trace the path of daily movement through the house. The circulation is illogical and highly inefficient.

- The Problem: A Maze to the Bedrooms. Imagine you are a guest who has just walked in the front door (via the deck) and wants to use the hall bathroom or go to a bedroom. The path is extraordinarily convoluted: you must walk through the entire living room, navigate around the dining table, cut through the kitchen’s primary workspace, enter the mudroom, pass what is likely the laundry closet, and then finally enter the bedroom hallway.

- The Real-World Consequences: This bizarre traffic pattern would create daily frustration. There is no direct or simple way to get from the public living spaces to the private sleeping spaces. Carrying a sleeping child from the living room couch to their bedroom becomes a long and awkward journey through multiple utility areas. The house feels less like a unified home and more like two separate apartment wings connected by a series of back hallways.

Step 3: The Second Flaw – The Mudroom as a Central Hub

This plan completely misunderstands the purpose of a mudroom.

- The Problem: A mudroom is designed to be a transitional zone—a buffer between the dirty outdoors and the clean indoors, typically connecting to a secondary entrance like a back door or garage door. In this design, the mudroom has been made into the central corridor and main artery of the entire house. All traffic between the living area and all three bedrooms is forced to pass through it.

- The Functional Failure: This defeats the entire purpose of the mudroom. Instead of containing clutter, it ensures that the mess of shoes, coats, and backpacks is constantly in the way of everyone trying to get to their bedroom or the bathroom. It ceases to be a functional utility space and instead becomes a cluttered, high-traffic hallway.

[Image showing a floor plan with red dotted lines indicating a long, convoluted path from the living room to the bedrooms]

Step 4: An Architect’s Perspective on Intuitive Design

“This floor plan is a fascinating example of a designer prioritizing a feature list over the fundamental experience of living in a home,” says Jennifer Miller, a (fictional) residential architect. “They succeeded in squeezing in ‘three beds, two baths, and a mudroom,’ which looks great on a real estate listing. But they failed to consider how a family actually moves through a space.”

“Good architectural design is intuitive,” Miller continues. “The flow should feel natural and effortless. The path from the main living area to the bedrooms should be one of the shortest and simplest in the house. This plan makes it the longest and most complex. It’s a classic case of winning the battle on features but losing the war on livability. A home shouldn’t feel like a puzzle you have to solve every day.”

Conclusion: Flow is the Feature That Matters Most

This compact home plan serves as a crucial lesson for anyone looking to build, buy, or renovate. A list of amenities can be seductive, but the true measure of a design’s success is its flow. A home’s layout should support and simplify your daily routines, not complicate them.

Before you commit to a floor plan, imagine yourself living in it. Trace your most common paths with your finger. If the journey from the couch to your child’s bedroom involves navigating through the kitchen and a cluttered mudroom, it’s a clear sign that no matter how many walk-in closets or covered porches it has, the design itself is fundamentally flawed.