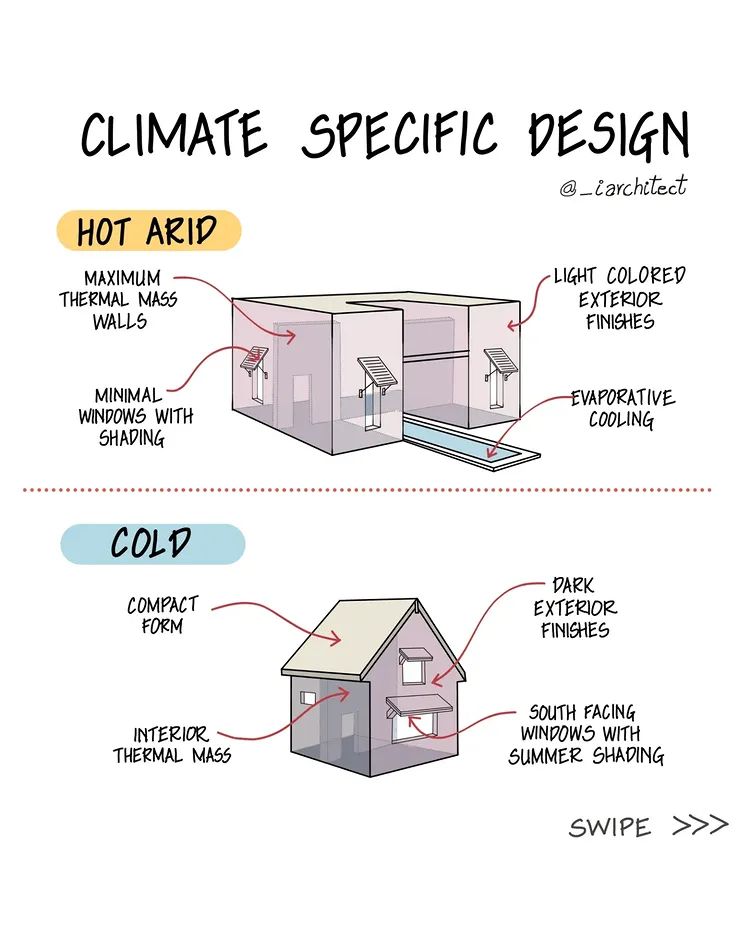

An insightful architectural diagram from the design account @_iarchitect is helping people understand a vital concept: Climate-Specific Design. The graphic clearly contrasts how a home should be built in a hot, arid desert versus a cold, snowy region. It’s a fantastic introduction to the idea that smart construction works with the local climate, not against it.

However, the diagram leaves a critical question for the millions of people living in the world’s tropical belt: Where do we fit? The vast regions of Southeast Asia, Central Africa, the Caribbean, and South America are neither dry deserts nor frozen landscapes. They belong to a third major category, Hot and Humid, which demands its own unique architectural rulebook.

The Fortress Home – Designing for the Hot Arid Climate

The first design in the diagram is for a hot, dry climate. The architectural strategy is defensive, creating a shelter that protects its inhabitants from the extreme daytime heat.

- Maximum Thermal Mass Walls: Thick, heavy walls (adobe, concrete, rammed earth) act like a thermal battery. They slowly absorb the sun’s intense heat during the day, preventing the interior from overheating. At night, when desert temperatures often drop significantly, the walls gradually release this stored heat, keeping the inside comfortably warm.

- Minimal Windows with Shading: To limit the amount of sun entering the home, windows are kept small and are deeply shaded.

- Light-Colored Exterior Finishes: White or pale surfaces reflect the harsh sunlight, minimizing heat absorption.

- Evaporative Cooling: The dry air makes evaporative cooling highly effective. Fountains, pools, or misters cool the surrounding air as the water evaporates, creating a refreshing microclimate.

The Insulated Box – Designing for the Cold Climate

The second example is the complete opposite, meticulously designed to capture and conserve heat in a cold environment.

- Compact Form: The structure is designed with a low surface-area-to-volume ratio (often cube-like) to minimize the area through which precious heat can escape.

- Dark Exterior Finishes: Dark surfaces are used to absorb as much warmth as possible from the sun.

- Sun-Facing Windows: Large windows are oriented to face the sun’s path in the sky during winter, allowing for maximum free solar heating. These are often shaded by overhangs that block the high-angle sun in summer to prevent overheating.

- Interior Thermal Mass: Heavy materials like concrete floors are located inside the home’s insulated shell. They soak up daytime solar heat and radiate it back into the living space throughout the night.

The Missing Climate: Designing for Hot & Humid Regions

So, how should a home be designed in a hot and humid climate? The key mistake is to simply copy the “Hot Arid” model. The crucial difference is humidity, which fundamentally changes the rules of comfort.

In a humid climate, the air is saturated with moisture, which prevents sweat from evaporating effectively and makes people feel sticky and hotter than the actual temperature. Furthermore, nighttime temperatures do not drop nearly as much as they do in a desert. The primary architectural goals, therefore, are to maximize airflow and provide constant shade.

Here’s how the Hot & Humid strategy differs from the Hot Arid one:

- Thermal Mass – A Potential Trap: The “maximum thermal mass” walls of a desert home can be a major disadvantage in the tropics. Because the nights are also warm and humid, the thick walls never get a chance to release their stored heat to a cool exterior. Instead, they continue to radiate heat into the house all night long, creating unbearably stuffy conditions. Lighter construction that sheds heat quickly after sunset is often more comfortable.

- Windows – Open and Abundant (but Shaded): Rather than “minimal windows,” a tropical design thrives on large, operable windows, vents, and openings on multiple sides of a room. This encourages cross-ventilation, keeping air moving across the skin. It is absolutely essential, however, that these openings are completely protected from direct sun and rain by deep roof overhangs, verandas, or breezeways.

- Evaporative Cooling – Useless: In air that is already moisture-laden, evaporative cooling has almost no effect. The focus must be on air movement, not adding more moisture to the air.

The Breathing Home: A Global Tradition

Dr. Isabela Rossi, a (fictional) global consultant on tropical architecture, confirms that successful design in these regions is about embracing the elements, not fighting them.

“The diagram is a great starting point, but it shows the danger of incomplete information,” Dr. Rossi explains. “Applying a desert design to a tropical region is a classic mistake. You see this in the wisdom of traditional architecture across the tropics. From the Bahay Kubo of the Philippines to the Palafitos of South America, you see common themes: lightweight structures elevated on stilts to capture wind and avoid ground moisture, open-plan living, and vast, steep roofs that provide shade and shed torrential rain. The goal is to create a home that breathes.”

In conclusion, climate-specific design is more nuanced than a simple hot-versus-cold binary. True sustainability and comfort come from a deep understanding of the local environment—including its humidity, rainfall, and wind patterns. For the millions living in the world’s hot and humid regions, the most effective home is not a sealed fortress, but a light, airy, and breathing structure designed to live in harmony with the tropical air.