Frank Lloyd Wright’s iconic design in Chicago continues to inspire architects worldwide with its harmony of form, function, and freedom.

In the world of architecture, there are certain buildings that transcend their physical presence and become symbols of innovation. Among them stands the Frederick C. Robie House, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright in 1909. Located in the Hyde Park neighborhood of Chicago, this residence is celebrated as the ultimate expression of Wright’s Prairie School movement, a uniquely American style that rejected European traditions and embraced the horizontal expanse of the Midwest landscape.

The Robie House is not just a building; it is a story of modern architecture’s beginnings, where form met function, and design was deeply connected to its environment.

1. Prairie School Style: A New American Identity

In the early 20th century, American architecture was heavily influenced by European styles—Gothic, Victorian, and Beaux-Arts. Wright, however, envisioned something different: a style rooted in the American Midwest.

The Prairie School emphasized:

Horizontal lines that echoed the flat prairie landscape.

Low-pitched, overhanging roofs that blended with nature.

Open floor plans, promoting freedom of movement.

Integration of indoors and outdoors, with terraces and gardens.

The Robie House became the perfect manifesto of these ideas, redefining what a family home could be.

2. Exterior Design: A Symphony of Horizontality

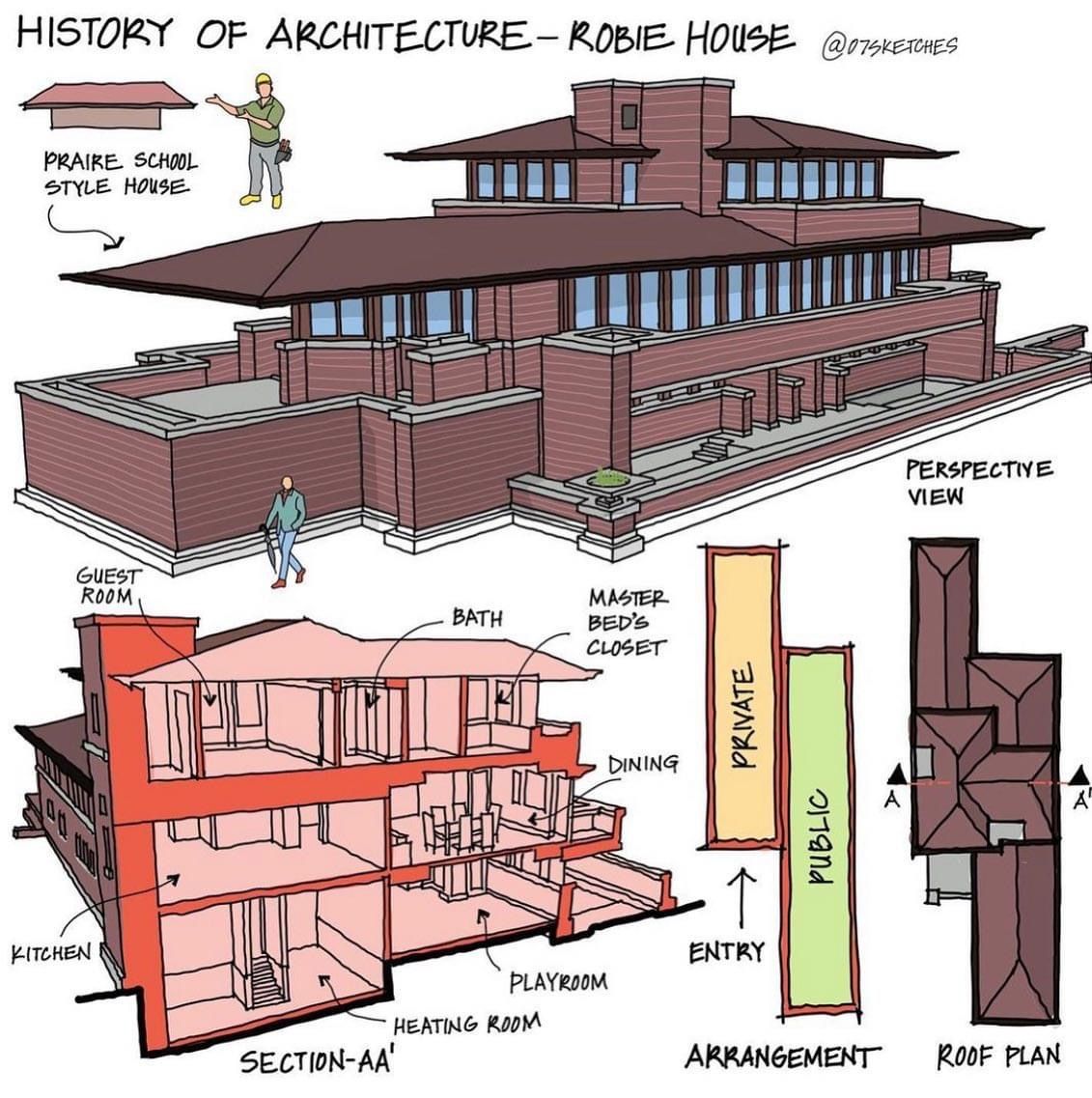

The first impression of the Robie House is striking. Long rows of brick and limestone bands stretch outward, almost hugging the earth. Its flat rooflines and deep overhangs emphasize stability and shelter, while the continuous rows of windows bring light inside and blur the boundary between interior and exterior.

Unlike traditional homes that emphasized vertical grandeur, the Robie House celebrated horizontal fluidity, creating a sense of openness that resonated with the American landscape.

3. Interior Layout: Function Meets Freedom

Inside, Wright challenged the boxed-in, compartmentalized rooms of Victorian homes. Instead, he introduced an open floor plan.

According to the section diagram:

Ground Floor: Spaces like the kitchen, heating room, and playroom highlight functionality and family life.

Main Floor: Public areas like the dining room and guest room flow into one another, designed for social interaction.

Upper Floor: Private areas, including the master bedroom and closets, ensure intimacy and retreat.

This layering of spaces—public, semi-public, and private—was a groundbreaking concept, later influencing countless modern homes and even today’s open-plan apartments.

4. Arrangement: Public and Private Harmony

One of Wright’s genius ideas was the clear division of public and private zones. The arrangement diagram shows this separation:

The public section (entry, dining, living spaces) was designed for gathering and hospitality.

The private section (bedrooms, baths, closets) remained secluded, ensuring comfort and privacy.

This balance of openness and intimacy made the Robie House not only beautiful but also practical for family living.

5. The Roof Plan: Protection and Continuity

The roof plan reveals a careful layering of flat and angled forms. Wright designed the overhanging eaves not only for aesthetic purposes but also to provide shade in summer and allow sunlight in winter, an early example of passive climate control.

This connection to nature was central to Wright’s philosophy: architecture should not dominate the landscape, but rather coexist with it.

6. Innovations That Were Ahead of Their Time

The Robie House introduced concepts that were revolutionary in 1909 and remain relevant today:

Open Concept Living: Eliminating unnecessary walls, creating fluidity and interaction.

Built-in Furniture: Wright often designed furniture to match the house, ensuring harmony between structure and interior.

Integration with Nature: Terraces, planters, and windows invited the outdoors inside.

Climate Responsiveness: Roof overhangs, orientation, and window placement optimized natural light and ventilation.

In many ways, the Robie House predicted today’s sustainable and minimalist design movements.

7. Legacy and Recognition

Despite being over a century old, the Robie House continues to inspire. In 1963, it was designated a National Historic Landmark, and in 2019, it was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List as part of “The 20th-Century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright.”

It is not only a Chicago treasure but also a global symbol of modern architecture. Universities, architects, and design students from around the world study its floor plans, rooflines, and philosophy.

8. Beyond Architecture: A Cultural Icon

The Robie House is more than brick and mortar; it is a reflection of cultural change. At the time of its creation, America was shifting from rigid traditions to progressive ideals of freedom and individuality. Wright captured this spirit in architecture, designing a home that was forward-thinking, democratic, and deeply human.

Conclusion: A Timeless Inspiration

The Robie House stands as proof that architecture can be both practical and poetic. Its Prairie School style was not just about aesthetics but about creating harmony between human life and the environment. Frank Lloyd Wright’s vision turned a simple residence into a masterpiece of modern living, one that still influences homes, offices, and even skyscrapers today.

As architecture continues to evolve in the 21st century—with sustainability, openness, and integration at its core—we realize that Wright’s lessons from the Robie House were not just ahead of their time; they were timeless.

Because the best architecture, as Wright believed, is not about buildings—it’s about better ways of living.